As your organization grows, it’s important to start establishing structure — not necessarily to allow for either a flatter or more hierarchical organization— but to enable innovative product and service ideas to surface, from the intern to the COO.

This is an important early organizational step because employees tend to take their ideas to various leadership team members as inspiration strikes. This causes chaos since no methodology is in place to effectively capture and vet new concepts, and determine whether or not the organization should act upon them. This post walks you through the steps of structuring innovation.

Structuring Innovation: The Business Concept Template

Here’s a great example of a simple tool that delivers powerful results. Create a shareable spreadsheet or document (e.g., using Google Docs) where people can describe their ideas, categorized by what the leadership team has determined are the main business drivers.

These categories may vary depending on what industry your business is in. For example, a manufacturing company’s drivers could be quite different than those of a tech services business.

The description of the idea should succinctly overview salient details, such as:

- Concept

- Value Proposition

- Proposed Market Test

- Drivers (i.e., Brand Equity, Customer Acquisition, Customer Retention, Average Order Value, Cost Reduction, Operational Efficiency, Social Impact, etc.)

- Enablers (i.e., Infrastructure, Human Resources, Specialized Skills, etc.)

- Required Resources (i.e., Executive, Marketing, Sales, Supply Chain, Operations, Finance, Legal, HR, etc.)

- Red Flags (e.g., any obstacles or barriers to success)

- Estimated Investment (Time and Human Resources)

- Expected ROI

This tool provides a construct that empowers people to contribute. Everyone knows they can use it, regardless of their respective roles within the company. The result is a greater, shared sense of engagement.

It also provides a way to build idea generation into whatever the product or service development roadmap is. Your roadmap will clearly have its own cadence and needs, depending on customer requirements. But, the tool can be worked in at scheduled points as it makes sense for your business — quarterly or monthly, depending on how young your company is and how fast you iterate.

Structuring Innovation: The Prioritization Process & Grid

The ideal process is to assemble a review team comprised of executive and senior leadership participants who sit in on all reviews. Each person with an idea is provided the same allotment of pitch time — approximately 5 minutes, with another 5 minutes set aside for questions and summation.

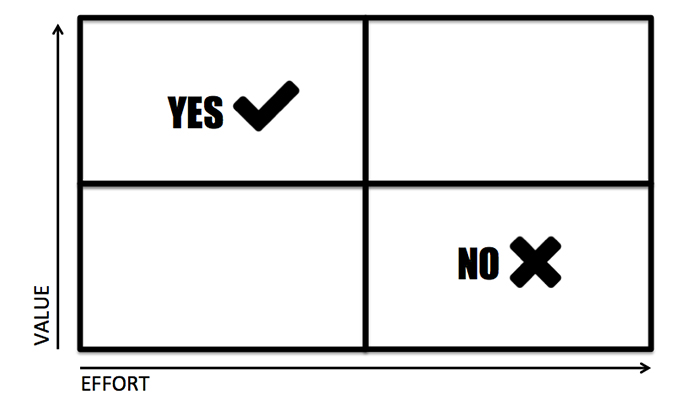

During the pitches, no feedback should be provided on the ideas. After all of the ideas have been heard, the review team organizes them by priorities. For each idea, the team scores it in a 2×2 table of low or high VALUE on one axis, with low or high EFFORT on the other axis.

The low value-high effort ideas automatically get knocked out. More than likely, the same is true for the low value-low effort ideas, although in some cases, they may get put on the ‘To Do’ list because they are a minimal distraction and are a passion project for someone.

The high value-low effort ideas get automatically advanced for a final review. The high value-high effort ideas are the ones where the majority of discussion is likely to occur among the leadership team. In these situations, one means of advancing the idea towards action is to seek a business plan or, at least, a more robust workplan describing how the idea would be produced.

It’s important to note that, if an idea from this process gets advanced to the product roadmap, then, more than likely, something else that was on the roadmap must come off of it, or at least be de-prioritized. No company has unlimited resources and, thus, there is a clarity and, in a sense, ruthlessness that such rigor brings to product roadmap decision-making.

By following this process, the low-value ideas at least receive feedback, providing rationale for why they weren’t pursued. Additionally, you can encourage any team members who came forward with such ideas to “take another kick at the can” and resubmit an adjusted, more compelling pitch. This process affords a sense of fairness and a belief that there is genuine desire to get the best results from everyone in the company.

I find companies are far better off if they put something like this in place early. Otherwise, if and when you grow rapidly, suddenly management finds themselves inundated with ideas — from the ill-considered to the stellar — with no way to prioritize or vet them.

In summary, this construct is somewhat of a modern-day, digital turn on the historical suggestion box, with rigor and transparency around it. The beauty is that it allows for serendipity to occur in the product development life cycle and is a relatively light-weight process to adopt.